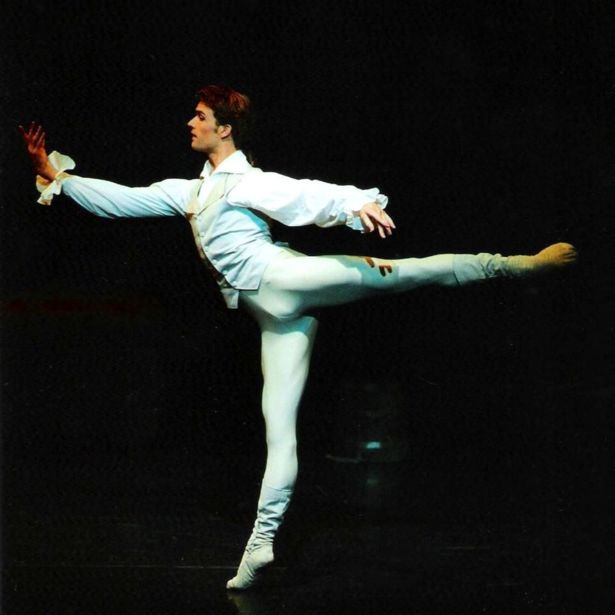

(c) Wilfried Hösl - Robert Tewsley in "Manon"

Deborah MacMillan (née Williams) is an Australian-born painter. She met Kenneth MacMillan in 1971 and lived with him for over 20 years until his death in 1992. Since then, she has carefully preserved her husband’s legacy. In this interview, which was carried out just before the revival of “Manon” at the Paris Opera, she speaks about Kenneth MacMillan’s work and about how his ballets are brought to ever new life.

Clement Crisp once said to Kenneth MacMillan: “your characters exist after curtain fall, they go on living. They live in our minds, they live in our understanding, just as they live in the choreography.” Why do you think this happened?

I think Kenneth had an inordinate ability to create movement that does not need words. He was not extremely articulate with words and he was very quiet. He sometimes said really fascinating things, but he was no great conversationalist. He would have found it very difficult, for instance, to sit here and do an interview. Therefore, the language of dance became his means of expression.

He always had an idea in his head and until he came up with movements that chimed with this idea, he rejected everything. I sometimes watched him choreograph, for instance when he created “Different Drummer”, “My brother, my sisters” and parts of “Requiem”, and I was always surprised. The dancers often created very beautiful shapes and I assumed that Kenneth would keep them, but he kept refusing everything. Therefore, I believe that he must have had a very clear vision of the story he was trying to tell. For him, movement was a means to an end; it was not an end in itself. It can easily become an end in itself because the audience remembers the beauty of a shape or a position, which is certainly backed up by posters and photographs with beautiful poses. But for Kenneth, dance was a language which he used to tell a more important story. In my opinion, all very powerful ballets transcend language.

He always had an idea in his head and until he came up with movements that chimed with this idea, he rejected everything. I sometimes watched him choreograph, for instance when he created “Different Drummer”, “My brother, my sisters” and parts of “Requiem”, and I was always surprised. The dancers often created very beautiful shapes and I assumed that Kenneth would keep them, but he kept refusing everything. Therefore, I believe that he must have had a very clear vision of the story he was trying to tell. For him, movement was a means to an end; it was not an end in itself. It can easily become an end in itself because the audience remembers the beauty of a shape or a position, which is certainly backed up by posters and photographs with beautiful poses. But for Kenneth, dance was a language which he used to tell a more important story. In my opinion, all very powerful ballets transcend language.

Maybe the strong impression the stories make on the audience is also due to the kind of characters he portrays? Many of them are not very “balletic”…

In fact, you sometimes see young dancers today who did not know Kenneth and who find it very hard not to be ballerinas. When Juliet dies on the tomb, she should really not die like a ballerina – she is a broken girl who stabs herself. Kenneth was always more interested in showing that than in knowing whether her feet were pointed or not, even though the technique was an important tool. But from time to time he requested, even required his dancers to drop the technique and do something that was more dramatically justified. Some dancers find that difficult.

Who or what might have influenced him?

He was marked by the fact that he grew up in the war, during which many terrible things happened. He lost his mother, which I think was an emotional problem throughout his life; he was a big chronic depressive. And then after the war so many new things happened in England. Cinema was incredibly important to him because it was his means of escape. At the same time, all the old pre-war dramatic ideas in the theatre were being thrown away by John Osborne and other post-war playwrights. It was a very exciting time. Kenneth was very good friends with John Osborne and thus he was caught up in an interesting group of intellectuals.

How did he position himself with regard to his predecessors, Ninette De Valois and Frederick Ashton?

Frederick Ashton was very much the founder-choreographer of the Royal Ballet. Kenneth admired him but he was aware that if he was going to make a mark he had to do something very different. Ashton’s works were very polite, very beautiful and classical and Kenneth probably felt that he should move away from that. I do not think it was a conscious decision; it just happened.

How was his relationship with John Cranko?

John and Kenneth were very good friends; John took him under his wing. When Kenneth started to get very bad stage fright it was John who suggested he come with him for a summer season at the Kenton theatre [in Henley-on-Thames]. He asked him to get involved there and to create a little ballet. John encouraged him and Kenneth certainly valued John; he thought he was a terrific talent.

Years later, when Kenneth wanted to create “Song of the Earth” and the Board of the Royal Opera House refused to let him do it, he rang John. Kenneth explained what he wanted to do and John replied: ‘come and create it for us!’ That immediately set up a working relationship where Kenneth felt safe. The same thing happened with “Requiem”, and then soon after that he choreographed “My brother, my sisters”. In Stuttgart, the dancers were closely involved with Cranko and the whole creative process. Kenneth could just slot in and they responded to him in the same way. At that time Stuttgart was a very young, thrusting, interesting company which had not yet had the dead hand of officialdom on top of it, which the Royal Ballet already had.

Years later, when Kenneth wanted to create “Song of the Earth” and the Board of the Royal Opera House refused to let him do it, he rang John. Kenneth explained what he wanted to do and John replied: ‘come and create it for us!’ That immediately set up a working relationship where Kenneth felt safe. The same thing happened with “Requiem”, and then soon after that he choreographed “My brother, my sisters”. In Stuttgart, the dancers were closely involved with Cranko and the whole creative process. Kenneth could just slot in and they responded to him in the same way. At that time Stuttgart was a very young, thrusting, interesting company which had not yet had the dead hand of officialdom on top of it, which the Royal Ballet already had.

When Kenneth MacMillan became director of the Deutsche Oper Berlin, did he also feel that he had the freedom to create something new there?

There was not the same opportunity as in Stuttgart. When Kenneth came to Berlin, there was already an established company, whereas in Stuttgart, John started something almost brand new. Although there had been a dance company, Cranko built something from scratch, whereas Kenneth was building on an existing work.

While he was in Berlin, Kenneth created a new “Sleeping Beauty”, which was a huge project, and he choreographed some other ballets, such as “Concerto”. He also went to Stuttgart to do “Miss Julie”, which unfortunately was not written down in notation. During that period, he and Cranko had some problem with each other and there was a sort of drama between the two. I did not know Kenneth at that time, but he later told me that it had been an unhappy time; he was drinking very heavily and he got quite ill. However, it was good for him to have that experience of directing.

While he was in Berlin, Kenneth created a new “Sleeping Beauty”, which was a huge project, and he choreographed some other ballets, such as “Concerto”. He also went to Stuttgart to do “Miss Julie”, which unfortunately was not written down in notation. During that period, he and Cranko had some problem with each other and there was a sort of drama between the two. I did not know Kenneth at that time, but he later told me that it had been an unhappy time; he was drinking very heavily and he got quite ill. However, it was good for him to have that experience of directing.

Where do you think his interest for the full-length ballet came from?

Firstly, he certainly had an eye on box office. Moreover, he became a director very early on, so he was aware that he had to provide roles for everybody in the company. When he was a director, he always tried to create ballets that everybody could take part in. Later when he gave up the directorship, on the contrary, he had much more freedom to produce work that did not necessarily give everybody a role. He also cut and tightened a lot of the ballets he had choreographed as a director.

Full-length ballets still work very well at the box office. It even annoys me a bit that the Royal Opera House almost exclusively shows “Romeo and Juliet”, “Manon” and “Mayerling” although Kenneth has done a lot of very interesting one-act ballets. But then they say that one-act ballets are difficult to sell. I think they could if they tried.

But of course there is always a great audience for a story. Look at the cinema, for instance. The most successful films are the ones with the big operatic stories, where money has been spent on making the story come to life, whether you use animation or great actors or other means. We always tell each other our stories; that is the human condition.

Full-length ballets still work very well at the box office. It even annoys me a bit that the Royal Opera House almost exclusively shows “Romeo and Juliet”, “Manon” and “Mayerling” although Kenneth has done a lot of very interesting one-act ballets. But then they say that one-act ballets are difficult to sell. I think they could if they tried.

But of course there is always a great audience for a story. Look at the cinema, for instance. The most successful films are the ones with the big operatic stories, where money has been spent on making the story come to life, whether you use animation or great actors or other means. We always tell each other our stories; that is the human condition.

Was Kenneth MacMillan particularly interested in literature?

Yes, he read all the time. Kenneth was a total autodidact: he had left school at 14 and was very aware of not being educated initially. I think people who teach themselves are always interesting.

In his biography on MacMillan, “Different Drummer”, Jann Parry notes that the idea of doing “Manon” came from Jean-Pierre Gasquet who first suggested it to Ashton and later to MacMillan. Is that correct?

Jean-Pierre Gasquet claims that he gave him the idea; I do not know whether this is true. I just think it was one of the books he had read.

Kenneth created “Manon” after “Anastasia”, which was a fascinating ballet with music by Tchaikowsky and Martinu. “Anastasia”, whose third act is set in a mental asylum, was breaking the mould completely at that time and it was savaged by the critics, which made Kenneth very depressed. Therefore, he was determined to do a ballet that would show the company off and that would correspond more to the standard structures of classical ballet. In “Manon”, there are three acts and there are ensemble scenes and solos and pas de deux. He said to me that it fitted much better in a nineteenth-century tradition than “Anastasia”.

Kenneth created “Manon” after “Anastasia”, which was a fascinating ballet with music by Tchaikowsky and Martinu. “Anastasia”, whose third act is set in a mental asylum, was breaking the mould completely at that time and it was savaged by the critics, which made Kenneth very depressed. Therefore, he was determined to do a ballet that would show the company off and that would correspond more to the standard structures of classical ballet. In “Manon”, there are three acts and there are ensemble scenes and solos and pas de deux. He said to me that it fitted much better in a nineteenth-century tradition than “Anastasia”.

How did he choreograph “Manon”?

Kenneth always started with the pas de deux: he used to say that they were the jewels and that everything else had to support them. They are the heights you have to come up to and come away from. He always looked to “Sleeping Beauty” as the cornerstone of the repertoire and used this ballet a template in order to determine how long each piece should be. He saw “Sleeping Beauty” as a model for the length of pas de deux, of solos, of divertissements.

Inevitably, what went on stage on the first night was a work in progress. That happens all the time in ballet because there are no previews like in the theatre. The dress rehearsal was open to the Friends of Covent Garden. Kenneth always disapproved of open dress rehearsals, but he changed his mind this time. Before the dress rehearsal, he came home and said: ‘I do not think the “drunken” pas de deux is working. I will have to cut it, but I cannot cut it until after the dress rehearsal, so it will have to go in front of the public and I am really worried.’ And then the pas de deux stopped the show as the spectators raved about it. When he came back from the rehearsal, Kenneth said: ‘I am not going to cut it after all.’ But he did not have that judgement until it got in front of an audience. That is why it is a shame that ballet companies do not get a couple of weeks of previews. As they are always in opera houses, there is no chance.

After some performances, Kenneth realized that some of his scenario was overwritten. He had tried, for instance, to give a role to Georgina Parkinson as the jailer’s mistress but then he recognized that it was not really helpful to introduce another character right before the end. I also made a cut in the port scene in the third act. Right at the beginning there was a scene with men leaping about; we cut that and now we start straight away with the women confronting the audience. I think this works better because at that point, you really need to get on dramatically. But those things happen after a long period of time. During the creation there is often no opportunity to cut.

Inevitably, what went on stage on the first night was a work in progress. That happens all the time in ballet because there are no previews like in the theatre. The dress rehearsal was open to the Friends of Covent Garden. Kenneth always disapproved of open dress rehearsals, but he changed his mind this time. Before the dress rehearsal, he came home and said: ‘I do not think the “drunken” pas de deux is working. I will have to cut it, but I cannot cut it until after the dress rehearsal, so it will have to go in front of the public and I am really worried.’ And then the pas de deux stopped the show as the spectators raved about it. When he came back from the rehearsal, Kenneth said: ‘I am not going to cut it after all.’ But he did not have that judgement until it got in front of an audience. That is why it is a shame that ballet companies do not get a couple of weeks of previews. As they are always in opera houses, there is no chance.

After some performances, Kenneth realized that some of his scenario was overwritten. He had tried, for instance, to give a role to Georgina Parkinson as the jailer’s mistress but then he recognized that it was not really helpful to introduce another character right before the end. I also made a cut in the port scene in the third act. Right at the beginning there was a scene with men leaping about; we cut that and now we start straight away with the women confronting the audience. I think this works better because at that point, you really need to get on dramatically. But those things happen after a long period of time. During the creation there is often no opportunity to cut.

How did your husband invent the steps, at home or in the studio?

Kenneth always invented in the studio. At home, he listened to the music until he knew it backwards. It used to drive me mad because that was before personal stereos and he would just listen to it over and over and over again! Then after the ballet was choreographed, he did not want to hear a single note of that music ever again. By that time I had got to know it and I quite liked to listen to it, but Kenneth shouted: turn it off!

Did Kenneth MacMillan give dancers clear indications how they should interpret a role, or did he give them great freedom to build their own characters?

Once the choreography is finished, and the dancers have been part of that process, there are steps which are written down in Benesh notation. But obviously you do not want carbon copies; you do not want somebody to have so absorbed a video that they copy somebody else right down to the eyebrow lift. I think a reason why “Manon” still survives and why so many companies want to do it is that it gives dancers the chance to develop within their roles. Dancers are like musicians: they play the notes, but they will play them differently from somebody else playing the same notes. Therefore, the interpretation of a role is always a personal thing. I think this ballet lasts because dancers have latitude in their roles, and that makes it interesting for a ballet-loving audience that wants to see lots of different casts.

How do you proceed when one of Kenneth MacMillan’s ballets is restaged today in a new company?

First I send someone to the company, usually a choreologist, and if they agree that they can teach the ballet to that company and they have some ideas about casting, they discuss it with the Artistic Director and try to come to an arrangement.

As I am trained as a painter, I tend to have an input in the stage picture. Thus, for instance, I invited John B. Reed to light “Manon” in Paris and he said that all the white shirts are too white, they are too shiny. So I went to the wardrobe and asked them to dye the shirts down a bit because otherwise we could not get enough light on Manon without them flaring up.

I have also made some adjustments to the sets in the swamp scene. I think that the stage picture is important because that is what the lay person looks at.

As I am trained as a painter, I tend to have an input in the stage picture. Thus, for instance, I invited John B. Reed to light “Manon” in Paris and he said that all the white shirts are too white, they are too shiny. So I went to the wardrobe and asked them to dye the shirts down a bit because otherwise we could not get enough light on Manon without them flaring up.

I have also made some adjustments to the sets in the swamp scene. I think that the stage picture is important because that is what the lay person looks at.

What else is important to make the ballet look authentic?

All the elements are important, the lighting, all the dramatic input and the way the set is kept. I have taken “Manon” away from some companies because it is not looked after, if the production values are let slip and certainly if the choreography is changed. I am very sensitive about that. You cannot control it totally, but you can let people know that you will react if the ballet is suffering… But on the whole, to my knowledge most companies try to do Kenneth’s work according to what the choreologists have insisted on, and they ask us to come back and revive it, which is very good.

How do you think MacMillan and Cranko managed to tell stories with out words and why does that seem so difficult at the moment for young choreographers?

If you are telling somebody a story about what happened to you, you tend to pick the words that have a meaning to get across the idea. A lot of choreographers forget that their steps are the words. And just because they create a beautiful pirouette or something makes a beautiful shape, that does not necessarily mean it is telling you anything except that it is a beautiful shape.

Moreover, even though Kenneth hated to get bad reviews because they made life very difficult, he was driven somehow to go on doing what he thought was right. Nowadays I think young choreographers are so obliged to create a success the first time round that the possibility of risking something is almost too much for them to bear. They know that if it is not a success, they are not going to get another job.

Furthermore, I think that they should learn to say no. Many new white hopes in choreography get a lot of offers and accept all of them. Kenneth refused a great many offers because he did not know the company and the dancers and thought he could not do it. He liked to work with dancers he knew and with whom he could immediately get onto a wavelength. Maybe he learned that from Cranko because Cranko did exactly that in Stuttgart. Cranko did some great work with his dancers who were basically his family. So he did not need to say much, he did not need to get to know them from scratch. They knew how he was thinking and he knew how they were thinking. There was no embarrassment between them and they would try anything in the studio. The sense of belief in what was being produced was paramount and that is a fantastic way to work. But if you jet in to a group of new dancers, you will of course just have to rely on well executed pirouettes and nice shapes. The audience will be pleased for a minute, the critics will be pleased because the art form is being supported, but I do not think the work is going to last.

Moreover, even though Kenneth hated to get bad reviews because they made life very difficult, he was driven somehow to go on doing what he thought was right. Nowadays I think young choreographers are so obliged to create a success the first time round that the possibility of risking something is almost too much for them to bear. They know that if it is not a success, they are not going to get another job.

Furthermore, I think that they should learn to say no. Many new white hopes in choreography get a lot of offers and accept all of them. Kenneth refused a great many offers because he did not know the company and the dancers and thought he could not do it. He liked to work with dancers he knew and with whom he could immediately get onto a wavelength. Maybe he learned that from Cranko because Cranko did exactly that in Stuttgart. Cranko did some great work with his dancers who were basically his family. So he did not need to say much, he did not need to get to know them from scratch. They knew how he was thinking and he knew how they were thinking. There was no embarrassment between them and they would try anything in the studio. The sense of belief in what was being produced was paramount and that is a fantastic way to work. But if you jet in to a group of new dancers, you will of course just have to rely on well executed pirouettes and nice shapes. The audience will be pleased for a minute, the critics will be pleased because the art form is being supported, but I do not think the work is going to last.

In those days, you could also rework ballets, as Cranko did with “Onegin” after he had got some very bad reviews for the premiere…

Exactly. “Manon” was also a failure. Some of the scenes seemed shocking at the time, but actually when you read the novel, it is all there. It is closer to the novel than either of the two operas based on “Manon”. This year I think it is the 24th company acquiring it and they all renew the license, which means it is very good box office and people keep coming to see it.

Who is in charge of the rehearsals for “Manon” in Paris?

“Manon” has been taught and produced by Karl Burnett, Gary Harris and Patricia Ruanne. She has coached all the roles and helped to stage the ballet, which has been wonderful as she worked with Kenneth when he first mounted “Manon” in Paris - and now I am seeing that the dancers are grabbing hold of the roles. During the last rehearsal, everybody in the corps de ballet was really doing their best to make sense of their character and the little stories that they concocted, so I am extremely pleased.

Interview by Iris Julia BURHLE

http://www.thefrenchmag.com/Iris-Julia-B%C3%BChrle-Contributor_a538.html

Interview by Iris Julia BURHLE

http://www.thefrenchmag.com/Iris-Julia-B%C3%BChrle-Contributor_a538.html

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H7YbobFLAA4

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J0dOnbUgFx4

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BElVftYksKM (Manon)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_pFlEwa0QSA ( Sir K. Macmillan)

http://http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lMqBsirpVxw (MacMillan's Mayerling Costumes)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ld3QBBrjemA (Mara Galeazzi and Edward Watson in "Mayerling")

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WgxqhpSxFdc ("Manon" with Alessandra Ferri and Robert Tewsley)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J0dOnbUgFx4

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BElVftYksKM (Manon)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_pFlEwa0QSA ( Sir K. Macmillan)

http://http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lMqBsirpVxw (MacMillan's Mayerling Costumes)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ld3QBBrjemA (Mara Galeazzi and Edward Watson in "Mayerling")

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WgxqhpSxFdc ("Manon" with Alessandra Ferri and Robert Tewsley)